The battle was part of the Second Macedonian War, in which Philip V of Macedon faced Rome.

Philip had fought the Romans before in the First Macedonian War, but since that ended with peace had been supporting Illyrian pirates.

An appeal for help by Athens was the perfect pretense to attack him.

Titus Quinctius Flamininus, the Roman commander, managed to force a battle at Cynoscephalae.

The Romans fielded 20,000 legionary infantry, 2,000 light troops, 2,500 cavalry and,

in a surprising reverse of the usual setup, 20 war elephants.

Against them Philip had 16,000 phalangists, 4,000 light infantry, 5,000 mercenaries and 2,000 cavalry.

On approach, both armies were drenched by a heavy rainstorm and the morning after the land was covered in thick fog.

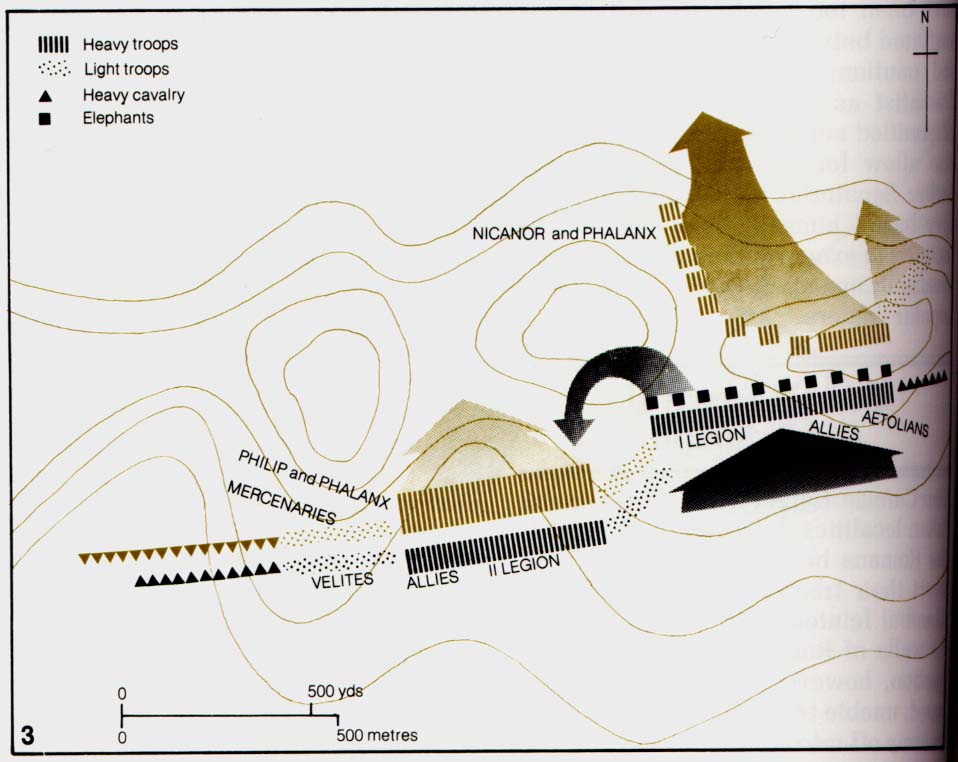

Philip sent ahead a small force to take the Cynoscephalae hills ("Kynoskefalai" in Greek, 'dogskull').

The Romans sent some cavalry and light infantry to scout too and these clashed with the Macedonians.

Both sides sent reinforcements to the ever larger growing battle on the hills, which first swung in favor of the Romans, then the Macedonians.

Philip, though wary of the rugged terrain, nonetheless got his phalanx to catch up and deploy on the hills.

In the meanwhile Flamininus lined up is heavy infantry as well.

He concentrated his forces on the left and had the right wing hang back, screened by his elephants, as he was not certain where the other enemy half was.

The Macedonians charged down the hill and pressed the Roman left flank back, but did not manage to break their line right away.

Flamininus, who had been commanding it, now switched to the right and ordered an attack there.

The Macedonian left had not fully deployed and immediately got into trouble.

When Flamininus ordered his elephants to charge, they broke and ran.

A tribune on the right, close to the center, who saw the development of the battle, took 20 manipels

and swung them left to attack the Macedonian phalanx in the rear.

The phalanx was not able to turn around as quickly and being vulnerable on the flanks and in the rear, was quickly defeated.

They phalangists lifted their sarissas in a token of surrender, but the Romans did not understand it and slaughtered them.

The Battle of Cynoscephalae is often said to show the superiority of the more maneuverable Roman manipels against the rigid lines of the Greek / Macedonian phalanx.

Yet in flat terrain, when shielded on the flanks by light troops or terrain obstacles, it proved just as strong as the Roman line.

Overall though, their tactical flexibility gave the Romans an edge.

In rough terrain they could exploit openings in the enemy line and engage the phalangists in close combat, where they were superior.

Philip lost about 8,000 men and 4,000 more were captured, against Roman losses of 2,000.

Philip himself managed to flee, but had to pay 1,000 talents of silver and disband his navy.

Macedonian power had suffered a heavy blow; never after were they able to mount an offensive against Rome.

War Matrix - Battle of Cynoscephalae

Roman Ascent 200 BCE - 120 CE, Battles and sieges